The Bayside

Dead Fern Press, First Prize Winner, February 2021

SugarSurgarSalt, February 2025

Principles

Your family chose the bayside, not the part of town closer to the ocean where I always stayed with my friends. You liked the economy, the savings. Why buy a five dollar ice cream when you can get a half gallon for less? Only fools bought ice cream cones. Your sister told me once you and your family were highly principled people. I thought this an admirable idea, but I could not say the same about myself. I just wanted an ice cream cone, even if it cost five dollars, even if it cost ten. I wanted so much to think the house you rented nice enough, but I quietly preferred renting on the side over the bridge, by the sea.

Kept Woman

Published in Trembling With Fear, January 2021 and Metastellar, July 2021

Now, there is no Fred. Now, I am no longer obese, incontinent, hairy, stained, paralyzed, starving, thirsty, sunburned. I am no longer sleeping on the floor, my face pressed into the toilet base. Now, I am free, but I am still here…

(Read the rest at link above.)

Yellow Out There

Yellow Out There

The community garden, known as Spring Garden, dazzled Sarah with its array of flowers and green extensions, the many tentacles and bursts of color that meandered within its gate and occasionally found their way, in little bits, out beyond. The gate - dark and elaborate and spiky with metal figures of birds perching forlornly on the tips of iron bars - was in itself tantalizing. And of course, Sarah’s eye caught more and more yellow each time she stopped to contemplate the intriguing garden.

There were maybe one hundred plots, fascinating in their differences. Some had tomato plants, some raspberries, some roses, some even corn. Sarah never once thought of growing broccoli, but here she could see an elderly man snapping it from its stem and placing it in a canvas bag hanging over his shoulder. She smiled at the scarecrows and garden chairs populating the garden. Picnic tables suggested people had dinner there, parties on the fourth of July, though she had never seen such gatherings.

With each minute she spent staring inside the garden, Sarah knew she was waiting, but

she had no idea what for. And the garden became, in her mind, the image of waiting. The

seeds waiting to grow, the plants waiting to get watered, the weeds waiting to be tall enough to pull.

“It’s so alive," she said to no one, breathing into the hot air which surrounded her, permeated the neighborhood. A gray cat, also a garden regular, wore a silver heart hanging from her white neck and often wove herself between Sarah's legs, brushing into her for comfort, reminding Sarah of where she was, that time was passing. Yes, Sarah was waiting too. Was waiting a good way to spend one’s time? What did the plants and flowers have invested in the future?

Sarah loved to imagine a fantasy garden plot. If she had her way, her plot would be filled with wildflowers, daisies, tiger lilies. Maybe she would grow vegetables like broccoli, but what she dreamed of was something impractical, something wild. Something thirsty that she could water and that would drink, something beautiful and vibrant she could cut and bring to her slowly dying mother, Molly. Pushing aside these dreams, Sarah’s mind always nagged with the knowledge she must turn away, walk her bike up the street, head home.

"Hey," Celly, Molly’s home health aide, said as Sarah let herself into the stuffy house.

"It smells bad in here," Sarah said, instantly realizing how accusing she sounded. "Sorry, Celly, I'm sorry."

"No problem, sweetheart." Celly was wiping down the counter, getting ready to leave.

The silence in the house was no longer a shock. Molly hadn't spoken in months. She just looked out of scared eyes like a lonely lost child. Some in the late stages of Alzheimer's grow belligerent, angry. Molly was as docile as a pussycat, alarmingly so. Sarah missed her spitfire, well-read, fifth grade teacher mother who could answer all the questions on the evening quiz show and complete the crossword every day, her hot cup of coffee by her side.

Sitting in her usual chair next to Molly’s bed that night, Sarah thought of all of the wildflowers at Spring Garden, and wished she had time to care for other living things. She reminded herself to buy her mother flowers at the market the next day.

Sarah closed the door, passed through the hallway and down the stairs, warmed by all the yellow, everything painted yellow, Molly’s favorite color. In the living room she looked for a book bought years before, Container Gardens by Number, something that Reader’s Digest had published, a cheap soft-covered thing. Molly had used this book to learn how to make beautiful arrangements in anything that would hold dirt outside their house. Visitors would always comment on her adept abilities with a box of mud and a few plants. Molly shrugged off the compliments. “I'm just a recipe follower," she said.

Her mother’s handwritten Post-it notes were stuck throughout the book. Sarah felt the usual stab of pain when confronted with a remnant of "before." She listened to the tall hall clock tick as she moved her head back to rest against the couch. Sarah let all of Molly’s containers wither up and die. Everything besides work and Molly seemed so overwhelming.

#

They had lived in this house together for Sarah's whole life.

"I’m lucky to have this house, honestly I am, but I swear if only I could paint it yellow. I have dreamed my whole life of a yellow house, really." Molly reminded Sarah of Anne of Green Gables, how Anne was constantly dreaming of hair another color besides red. Nevertheless, they compensated for the brownstone exterior by painting every room inside a different shade of yellow. Molly's bedroom was a butter yellow.

"It's almost not yellow, almost cream, but at the same time it's a perfect yellow!" Molly said, satisfied, on the day they painted it. Sarah's room was what they both called lemonade. "What would you say Sarah? A brighter butter? A butter turned up a notch?"

They called it the yellow project. Sarah could still picture her mother with paint all over her jeans and sweatshirt and old white canvas sneakers, her short hair covered up in a bandana, hands on her hips. Sarah liked to find different shades of yellow to add to the list they kept on a bulletin board in the kitchen. They perused the many catalogues that dropped through their door mail slot, noting the numerous nuances of yellow, recording colors like burnt sunrise and honeyed umber.

"It gives you hope, doesn't it?" Molly said, flipping the pages, "All that yellow out there?"

#

One day, gazing into Spring Garden, Sarah heard an older man's voice shouting over the corn stalks. "What’re you doin’ over there?"

Sarah jumped, then froze. "Um-I.." she began to say.

He laughed, "I knew I'd scare ya!!"

She smiled weakly and remained frozen in her place, staring at the green pumpkins connected to their vines.

The sight of the pumpkins provoked a dark shade across Sarah’s mind. The doctor said Molly would not see another fall.

"What, don't you like pumpkins?" he said, coming over and taking out a cooler from underneath his workbench. He produced a little paper cup out of nowhere, filled it with a purple drink. "Take this," he said, reaching his hand out through the bars of the fence.

Sarah felt shy but predicted this man would not take no for an answer. She gulped it down, finding she was really very thirsty. She stared at him for a second as she finished her drink, looking into his face in the late afternoon sun, the comers of his eyes revealing deep wrinkles. His skin was a kind of intense earth with hints of orange.

"I'm Vince," he said, sort of gasping after his drink. "I work around here."

Sarah didn't know if he meant in the garden or the neighborhood. "What do you do?" she said.

He left the pumpkins and started furiously digging up a rose bush. "Landscape, plumbing, moving, pool maintenance, you name it. Need something done?"

"Wow! No, I was just curious. I'm surprised you have time to have a garden."

"Always time. You should come and garden. You look like you could use some sun," he stopped what he was doing and squinted at her.

Sarah noticed the stain of sweat lining the bandana wrapped around his head. "I have too much to take care of already," she said, looking down, then away, becoming self-conscious by the familiarity of the phrase.

"Ha! Get busy livin’ or get busy dyin’! Where’d I get that?" he asked, pushing his worn boot on the top of a spade. Then he stopped, and reached in his pocket. "See these keys? One's for the gate, one's for the shed. You can have them. You can come in and work in my plot, whenever you want. Weed, water, cut some flowers from over there," he pointed to a bank of wildflowers and wiped his grimy face on his shoulder.

"I have work -" Sarah said.

“Ha!" he repeated in reply.

#

It felt strange to Sarah, to enter the garden for the first time as she did the following Monday. She looked at her watch as she entered, knowing she only had about twenty minutes. The gate opened easily, no sign of Vince, so she walked slowly toward his shed, unlocking that door next. She surveyed the darkness and immediately noticed a bench with a collection of garden tools thrown across it. Underneath a dirt-encrusted spade, lay a sprawled handwritten note on which she deciphered the words, It's about time!

On her next visit, she made sure she left work a little earlier, making an excuse about her mother and feeling guilty for doing so, but getting out the door at four just the same. This time she took the red-handled shears that were on Vince's potting bench and began dead-heading. She loved the catharsis of removing the dead ends of things. His basil looks dry. She looked around for a hose, seeing one nestled between rows of com. She approached the green snake, feeling by its coldness and wetness that it had been used, and recently. She pressed the spray gun and saw an arc of water shoot forth. Dragging the weighty green coil over to the desired destination, she drenched Vince's herbs. When she was done, she went to drop the hose back where it was, but instead she followed its trail through the garden, wishing to see where it began, what different living things were in its charge.

Another time, down on all fours with her hands stuck straight into the mud, she dug deeper and deeper, and, moving further down she detected the earth getting richer and darker. She felt worms and small rocks. It was not until she stood up and mopped her forehead and took a sip of water, that she realized tears were mingled with the salty streaks of sweat on her face.

#

Always, she snipped the yellowest wildflowers from the garden and, after returning home, put them in a tall glass vase beside her mother's bed, softly recounting for Molly the sunshine yellow, the honey yellow, the shady yellow. Sarah looked down at the dirt in her short nails and then around the still room. She knew there was no point in reading, Molly didn’t seem to notice anymore. The flowers do brighten this room the tiniest bit. She listened to the air conditioner humming softly. Sarah sat quietly, thinking, always to herself.

Sarah regarded her mother's withered bird-like face, then stared at her own in the bathroom mirror. Is Molly busy living or dying? What about me? She was already thirty-five, she knew she didn’t have much to show for it. Some of her co-workers made small comments about “keeping her mother alive,” not-so-subtly questioning Sarah’s choices. All she knew for sure was that she needed to be right where she was, now. Everything outside of that, she didn't, couldn’t know. Would Molly see another fall? Sarah chose not to picture the winter months when Spring Garden would be devoid of color, the dried corn stalks blowing in the winter wind, just as she chose not to envision this room empty of her mother, the bed stripped, the door closed.

Sarah remembered a quote, "God gave us memories so we could have roses in winter and mothers forever." She didn't know who said this, but thought if she had her own plot in the garden she would put that quote on a stake and keep it there.

Left Unsaid

The Woven Tale Press, November 2020

Left Unsaid

Donny, 2012

“It’s so fucked up,” something I didn’t usually say, was all I could muster. My brother was dying of cancer and that’s all I had. I was trying to be cool, acting like we were talking about something, anything, else.

“It is,” was his response, and all he ever said to me about the disease that would eventually kill him.

I said lots of stupid things to Donny instead of talking about his reality, and he pretty much played along. Two months before his death, I told him all about my trip to Austria. “I hope to get to Salzburg one day,” he said in reply. Around the same time, he told me he took his daughters to see a movie. I said, “I don’t like children’s movies.” When he told me he was tired, I said, “Oh, yeah, I’m exhausted too,” as though it was normal, as though we were all the same level of tired as someone with stage four lung cancer.

As his illness intensified, I felt the emptiness of our conversations bearing down on me. I went to Target and bought a journal with a blurry pastel cover. I was going to list every single thing I remembered. I was going to mail it to him in New Jersey. I pictured him reading it, sadly, but I could also see him laughing over memories. I wanted him to know how much all the little things added up for me, what an effect he had on me.

The journal sits almost blank up on my third floor now. I never was able to finish my list. He silently slipped away before I had a chance.

Mary, 2008

The woman who works at the Y, running and laughing alongside the cart of toddlers being pushed through the hall, is bald, eyebrowless, wearing a turban. Even after having three of my six siblings and several friends and acquaintances experience chemotherapy, I still feel the sneaking panic, the desire to stare or look away.

My oldest sister, Mary, has been bald for eighteen years. Most people don’t want to know you can get chemo for that long, but she has. Last July the count was 900 chemotherapy sessions. 900. She is 60 but is often confused for an old man. She once told me there are women wearing exceptional wigs and with such skillful makeup that you would not know they have cancer. It makes you wonder about all those secret cancer people, and how most people would rather it be that way.

In contrast, Mary calls it “the power of the bald head” and has acquiesced to its occasional effectiveness.

But when you are bald, people either avoid you entirely, insult you, or overshare. I remember once being at an event with Mary. She was winning an award, something to do with having cancer. Afterwards, I stood beside her as a line formed of well-intentioned people who wished to tell her about when they lost their hair or someone they knew who beat cancer or someone who died. One woman smiled sweetly at my sister and said with her cute Philly accent, “Don’t worry, honey, your hair will grow back. It will be beautiful.”

That was one of the days I got a peak into what it’s like to be a bald woman.

People just can’t take women losing their hair.

We would all rather not know about any of it.

Donny, 1990

I was surprised about his eyebrows. I never thought about eyebrows and eyelashes falling out. That night was when I learned that eyebrows are really important. Everything I knew about my brother’s face was different without his eyebrows.

Donny had a considerable red birthmark covering a large portion of his face and neck and chest. It was nothing to all of us, the family, but it was, looking back, the first of many unfair burdens he would carry in his life. People asked my mother if she burned him when he was a baby. One of my classmates in grammar school brought it up once in a group discussion. None of us noticed, to the point where I’d say, “What birthmark?” when someone unexpectedly mentioned it. There were many more important things about my brother than that birthmark, things people of course at first meeting would not know, maybe would never know.

The loss of his eyebrows made all his history, even the birthmark, disappear, he was featureless, disappearing into the crowd.

On this night, the night I noticed his lack of eyebrows, I was his booby prize date to see Fine Young Cannibals at Jones Beach. He couldn’t get anyone else to go and told me this outright. No hard feelings. This was Donny, my coolest brother, the one I wanted to impress. I was thrilled, although I am sure our conversation was stilted. It was the first time I’d seen him out after his chemotherapy treatments. He treated me to dinner at Sidekicks, the fancy-to-me restaurant on Broadway near the college all seven of us attended. I told him my college drinking stories over mozzarella sticks.

“Same play, different actors,” Donny always said in response to my stories.

This was his first bout (there would be three) with cancer. He was more prickly then, feisty, pissed. He hadn’t married yet, had kids.

Bald, eyelashless, I didn’t recognize him that night. We stood in the crowd at the arena. I went to the bathroom and when I came out, my brother stood in front of me and I had no idea who he was. I couldn’t pick him out of the crowd.

“Mag!” He shouted at me, a little angry, almost like he was waking me up. Annoyed, like this had happened to him before.

“Oh! Sorry!” I said. He just shrugged. We both pretended nothing happened, but it happened again at the end of the concert. Same deal- bathroom, crowd, no recognition, anger, annoyance, denial. On the way home, as he drove me back to my dorm in his red jeep, we sat in silence.

Mom and Dad, 2015

There’s not a lot that you can say that’s right when trying to tell your parents their son is dying.

There was the ticking clock, the round table where he loved to sit, drinking coffee, eating toast, pitching one-liners. He wasn’t there. He was in New Jersey, dying. There was nothing I could say to my parents that they would accept. They always switched into hope-mode. What parents readily give up on the life of their child? Especially Donny’s life, a life they’d been fighting and hoping for for years.

“Mom, they are out of things to try. They are just doing an immunotherapy drug as a last-ditch effort, but they know it won’t work.”

The ticking clock. The round table. The empty chair. A creak out of nowhere.

My mother’s face was resolute. Her hands were busy cleaning plates.

“Well, we just have to believe it will work.” With that, I walked out of the room in frustration. I wanted to prepare them, to help Donny by telling them, but after several attempts it seemed futile.

“Leave it to Donny to tell them, to explain,” my sister Bubsi had advised.

But he didn’t tell them. When he was told himself his first words to his wife were, “What will I tell Mom and Dad?” As though there must be a way to spin it, a verbal exit.

Rule #1: Do not tell your parents you are dying. The rest of us didn’t need to be told. We knew enough by now to know stage four lung cancer=death. All I had to see was a photo of my emaciated brother, with that look, that impending death look I had seen before on strangers, and the truth was crystal clear.

That day, Dad followed me out of the kitchen, down the long hall to the den. Where was I going? I didn’t know. I turned to see my father’s sagging shoulders behind me, his pleading eyes.

“Dad, we have to somehow face this,” I said, covering my face with my hands, sobbing. Dad’s arms encircled me, comforting his 46-year-old youngest child, something parents always know how to do. Certainly easier than saying goodbye.

Donny 2016

· You got lost as a very little boy after we moved from Connecticut to Newburgh, New York. You went to a neighbor’s door and said, “I’m Donny Doo from Old Saybrook.”

· You were famously carried off the playground by Mary, kicking your arms and his legs, enraged at some other kid.

· You beat up Joe Cantone on the sidewalk of Sacred Heart School outside the busses.

· When I was about twelve I got a Ralph Lauren polo shirt for my birthday, and, when I opened the box, I said dramatically, caressing the shirt, “My first Lauren.” You teased me about this for the rest of your life.

· Tears ran down your high school face at the dinner table after getting in trouble for your poor grades, the only brother out of three I have seen cry.

· You always paid for my dinner, even when I was well beyond thirty.

· You had a big, round head as a baby and sat and stared at a plant for many months, maybe years.

· You got in a car accident when you were a teenager. I remember the blood on your shirt by the washer the next morning. It was the first time we almost lost you.

· You picked us up from the pool in the summer and you’d tap the brake to the beat of Boz Scaggs on the eight track as we waited at lights.

· When you were little, your younger by one-year sister, Bub, sometimes dressed you for school.

· You would often sneak cash into my hand before saying goodbye.

· Every Bruce Springsteen song will always make me laugh and cry and think of you.

· You always picked me up at the train station, which wasn’t always convenient. Once, when the train was late and my trip got really screwed up, I started crying; you said on the phone, “Are you okay? Do you want me to come get you?”

Bubsi, 2011

The waves were turning and pulling out. On another day, in another life, I’d be calm, transfixed by nature. That day, the waves just sounded angry. Their relentless crash polluted my ears. Everything was harsh. The sand. The sun. The heat. The people. Even the children playing, burying each other, packing and patting sand sculpture, seemed sinister. All other beach goers obese or emaciated in their flimsy swimsuits. Everyone had a hairy backs or bellies, enormous boobs or butts. Conversations rose above the tiresome ocean, high-pitched laughter, an incessant seagull caw.

I removed myself from the circle of friends in beach chairs to speak to my sister on the phone. I was waiting for the call. My expression was pinched as I shoved a finger in one ear to hear her tell me her breast cancer had returned. My second sister, my third sibling to suffer this fate. Tears. My heart dropped to the ocean floor. “I’m sorry, Bub,” I gasped/screamed, despair rolling up in my chest, crashing.

Donny 1989

We didn’t know anything about cancer then. We were part of that persistent crowd who thinks cancer belongs to others, those who smoked or have the gene or did not get checked often enough, people who earned it, cancer people.

That early spring day I awoke in my dorm room as one of the others, the noncancer people. By late morning, I’d be walking down my sister’s dorm hallway, toward the window at the end where she stood in hazy light waiting to tell me that Donny didn’t have walking pneumonia, as we thought. He had cancer.

Now, I know how I’d receive that message. A sharp breath inward, a clenched fist, a tightening, protective muscle. Now I would first feel anger, and then I would direct my energy toward protection, control, a narrowing of focus. What I know now that I didn’t know then, is that cancer is a process: one must get in line, one must wait their turn, be patient, follow directions.

Back then, I just collapsed in tears, tears whose origin I could not fathom and whose energy and volume were extreme. My subconscious knew this was the end and a beginning. The choking of sobs was all I could show, the only sense I could make. Cancer was chemo, and then, not long after, death.

That’s all we knew about it then.

Mary, 2001

I stood on that 30th street platform hundreds of times, and I would stand there a hundred more, but I had never run into my sister there before. I picked her out easily, a bright head scarf emerging from the throng of commuters. She carried what to others might be an art portfolio. I knew even then it was not art, it was full of scans. She was coming from the renowned breast cancer doctor at the renowned institution nearby.

Onboard, we sat across the aisle, shouting above the rush hour din and the clunks and screeches of the train.

Palliative care, the new words I heard that day.

“I cannot be cured...so they just keep the cancer under control until…” Her voice, lost in the other conversations emerging from the crowd, her face, blank.

Was this what shock looks like? Do I look the same?

I remember only the uncomfortable figure of silence, a third sister, sitting, wedged between us, for the rest of the ride. The racket of normalcy pressed in on us, defined us as different from everyone else, or so it seemed.

Donny, 2015

I didn’t see my brother die as I imagined I would. Somehow, I assumed I would be there. There were lots of people there: Mary and Bub, their husbands, my brother’s wife and daughters, plenty of his many friends. But not me.

I was at the Dark Horse, dinner with a friend. I knew my brother was in the hospital, but it was at that stage where he was in and out a lot. The last text from Bub: Blood pressure good, breathing good, resting comfortably. I kept the phone beside me on the table. When the screen lit up, I saw it was a call and not a text. My body instinctively rose up and headed for the exit.

“Mag, you need to say goodbye to Donny now. He is slipping away. I am holding the phone to his ear.”

No time for explanations.

I crouched and cried into my brother’s dying ear. Leaning into a cold wall I searched my panicked mind for words, something good, something right. But I repeated one vague thing: “Donny, I know. I know everything.”

I hope every day he heard me and understood.

Honora 2015

My closest in age sister, Honora, and her husband, Toye, flew to New Jersey for a final visit. It was Halloween. Donny would be dead in 20 days. Trick or treaters rang the doorbell and his girls dressed up amidst oxygen tanks and the burden of impending death.

Later, Honora sobbed to me, “I was such a wimp.” While saying goodbye, she found she could not look him in the eye. He also averted her gaze.

I get it. Siblings can’t say goodbye. Won’t.

No matter how many times I go through this, despite my mind’s insistence on acceptance, my eyes will always want to look away.

Mary, 2019

Her 60th birthday, November, her last.

In July, beneath fairy lights, accompanied by the warm sounds of a Latin band staged on my patio, she told me what she would like for her party: “Karaoke and dancing.” I told her, with a semi-conscious air of gravity, “If that’s what you want, then that’s what you’ll get.” She smiled, exchanging a quiet knowledge of why this one was important. It could be because it was her 60th. It could be because she was told at 43 she would not live to see 45. But the quietest reason was that she was failing. Visible by her gait, her color, her pain, her spirit.

That night on my patio, she seemed, as she often did during the eighteen years of her stage four breast cancer, the younger sister. Before, she was always quite the opposite. Eleven years older than me, she helped my mother care for me when I was a baby, taught me, inspired me, guided me, annoyed me, yelled at me, pushed me, led me in so many ways. But that night she stood in my arms as we danced and stared at me with hopeful eyes, adding, “I think you are the most stylish person I’ve ever known.” During the years of her illness, for better or for worse, she relied on me for support, and I gave it as much as I could. But it was never enough.

For the party in November, my brother-in-law planned a beautiful Italian lunch. There were speeches by her sons, impromptu stories. Mary told all of us how much she loved us, how much family meant to her, how she dreamed someday of Nerz Road, a place where we would all live together, just houses apart. We were hushed as she spoke what felt like a final statement.

Back at the house, we made her wish come true. An Amazon strobe light transformed her living room into a Victorian disco. Spotify chugged out the Mary’s Party playlist full of seventies power tunes. Queen’s “We are the Champions” felt glorious as my siblings and nephews and in-laws and I stood with Mary and sang with Freddy and raged against cancer, holding our arms up in the air, swaying together. My husband and I have our own karaoke setup so everyone was playing with it, screaming lyrics to all our favorites. Mary’s son, Joe, sang “Party in the USA” by Miley Cyrus.

Mary got tired and put on her cozy pink robe, so did my five-year-old son, Pedro. They cuddled on the couch, snapped into a picture. For months afterwards, Pedro said it was the best party ever.

In 30 years of this cancer thing, never seeming to know what to say or do, this one was good, and somehow, finally, everyone said the right things.

Sick, But Sociable

What I Thought of Ain’t Funny, Malarkey Press, November 2020

Every priest has something, that one thing that is theirs outside of the religion. Some priests have pets, some priests love sports, some priests make their own beer. Greg’s thing was smoking, and Greg thought his best friend, Lou’s, was the jokes….

Libby in Four Seasons

Woman’s Way (Ireland), October 2020

Winter

I shave Jim’s face slowly each morning, savoring every second. I smooth the Barbasol onto his stubbly beard, grateful for the new growth, even though his body is slowly giving in. The stabs of manliness are miraculously still there, still sharp as I move the razor across his slack jaw. I revel in the rejuvenation of his skin, the smoothness he shouldn’t have, considering his condition, but still does. Harold climbs up on the bed, licks Jim’s fresh face. I lean down to sniff my husband and whisper our secret words (bear, pebble, cheesecake), kiss the last dollop of cream off his right ear.

Today, as I stare out of my house on the lake, I watch the snow falling down, breaking the grey screen of sky into swirling white specks. I am aware of the shift in the weather, and know my husband, my oldest friend, my first love, my second chance, will be gone by nightfall; his spirit sliding out, trading places with the whiteness, becoming part of its beauty, its resolve. It’s okay. We have had so much.

Spring

I don’t bake at Christmas like everyone else. I bake in the spring. April is technically spring but in these parts it feels like February. In April, I make my special cinnamon roll that looks like a lady’s long braid bent into a circle. I make eight total, one for Harold and me and one for each of the seven houses around the lake.

At each house people are surprised, stare at my frail stoop, my gnarled hand grasping a floral cane. They look a little scared, or maybe guilty. They ask me if I’m warm enough, if I want to sit, need a coffee, tea. They don’t want my cinnamon roll, but pretend they are delighted, touched. No one mentions Jim. I don’t mind, but I notice. Between Jones and Egans my foot goes into an unexpected hole and I lose my balance and fall, cutting my finger somehow on the way. It’s not a big spill, although Harold is beside himself, shaking in distress. He’s no spring chicken either. A slight, dull pain tiptoes down my spine. Is this how I will die? For so many of us old people, death begins with a fall.

“Oh for pity’s sake,” I protest as Harold barks and Jean Egan fusses.

“We really could pick up the danish, Libby, really.” It’s not a danish. I listen to her talking, but I really am just waiting, waiting to leave, to move on. Younger people often think they know everything, can fix everything.

Summer

Of course, August will always be for Craig. We are 25, newlyweds. We love the dry, hot air of Central New York summers, the cold nights, wrapping ourselves in blankets after night swimming. Unlike my serious young husband, I have no intention of working across the summer, and plan on dragging my paint into school in September and figuring everything out then. This house I grew up in and will spend my life needs work. The buttery walls beg for clean corners, throw pillows, painted tables. I work hard moving, sorting, scraping, painting, sweeping, piling up.

I start to feel hot and dirty and go upstairs to put on my purple swimsuit. I think better of it and peel off my sweaty clothes, pull on my robe, and run down the path. Shooting for the end of the dock, I let the robe fall to the wooden slats and without thought or hesitation, dive hard and fast into the green blackness. The smell of sulphury water is like entering the center of the Earth, and the sky seen from floating on my back feels like power and its opposite, smallness, loss. I shiver and flip.

At the house, police lights, alive with bad news, twirl and swirl in our driveway, but my eyes are busy staring down through the murkiness, observing the darkness and light.

Fall

Everything is quieter after a gunshot blast, even one I really never heard, experienced only in my imagination. Often, after Craig, I sit and listen in the silence.

I expect him. It is the year we turn 30 and Jim comes through the silence and knocks on my door. A funny look on his face and a daisy in his lapel, he trudges slowly on account of his health (He has already had one small heart “event”) up the path that leads to the house. I stare at him through the fantastic golds and oranges of autumn.

“What?” I feign annoyance, glance down at my long men’s shirt, one of Craig’s, green paint smeared on my cheek.

“Libby,” he says, huffing a bit. His dog, Patrick, paces behind him, his squishy brown nose sniffing the dirt, following my trail of memories, history, searching.

Big Girl Pants

I had been shopping for hours, looking for pants I could stretch across my postpartum form and that would improve my shape and restore some of my body confidence and sense of style. Tears filled my eyes in countless dressing booths as each pair of pants, in sizes I had never reached for before, pulled and strained across my wide girth. Things were feeling a tad desperate……

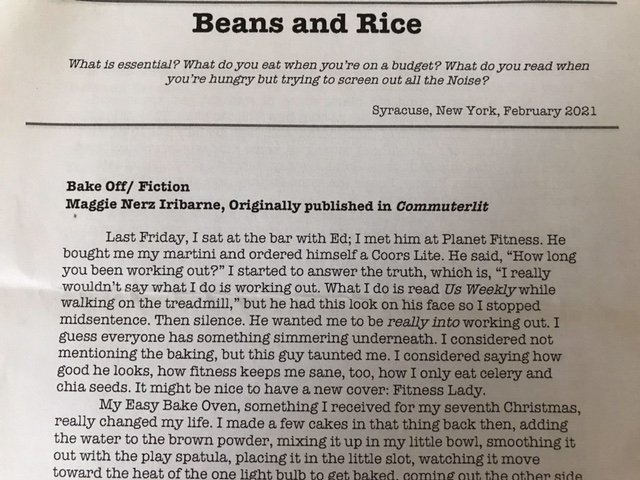

Bake Off

Beans and Rice, Issue 15, February 2021

Sex is calming, too. I’m pretty good looking, not bad, and, I discovered as I grew up that men other than my father like to hear about me baking. In high school, I would tell a lie to my male teachers about how I baked, even though I didn’t anymore. Cupcakes really turned them on. Perhaps they pictured my ass cheeks as cupcakes, tight little circles, covered in cream. Yes, please! Later, in college, I kept telling the lie about baking. Guys I met down at the bars licked their lips when I told them how I liked mixing and stirring, spreading and frosting. “Do you lick the bowl?” They ALWAYS asked that. Many still do. So predictable…

Of Love and Faith

My husband is the one with the faith and I am the one with the religion; that’s what I always say. I love and need Catholicism, the faith of my parents and siblings, but I am usually consumed by doubt and fear. My husband is a bright light, always sees the glass half full. He constantly assures me things will be okay. José resets me, tells me to focus on the good and not the bad. The light instead of the darkness…..

Gus

It all begins with an idea.

Gus was an orange tabby cat, like Morris from the Cat Chow commercials, the ones where the cat put his foot forward and back in a cute little cha cha cha dance move. He wore a big metal heart around his neck that said GUS, which he found really embarrassing and uncomfortable. Mary and Tom went overboard, Gus often thought to himself, too much food in his bowl, that crazy refilling water thing, and this heart with their names and address on the back. He knew it was because they felt guilty. They were always away somewhere, somewhere where there were lots of fish; Gus could smell it on them when they returned. They cut that flap in the kitchen door so Gus could come and go as he pleased, but it was more so they could come and go as they pleased, that was the truth of it.

He knew not all the other pet owners were like Tom and Mary. Gus had spoken to Fluffy two doors down, and she bragged about all the petting and snuggling she received. Gus was not the receiver of much petting. He wasn’t sure why Tom and Mary wanted him. They didn’t even have a mouse problem, which, according to Shivers on Gaberdine St., was the reason most humans got cats. Gus didn’t like mice; they were so defenseless. He got down just thinking maybe Tom and Mary could send him to the animal shelter. Gus’ friend Sassy went to the animal shelter.

The neighborhood, called Hamletshire, was nice enough. Lots of sidewalks and small houses in different colors. Lots of people walked their dogs on ropes. Gus was glad he did not require such restraint, but he did envy the attention the dogs got out on the sidewalk. He always saw humans stop to talk to the dogs, kneel down and let them lick their outstretched hands. He wondered why his nice, neat, sandy little tongue would not be more preferable, but, to each his own, that’s what Tom always muttered when Mary said something weird, which she often did. “Tom, I am going out to buy yoga pants at the studio sale!” She’d said things like that.

Gus was hungry. Hungry for food, attention, love. He remembered his mother, who called him a beautiful cat name that cannot be spelled and sounded like some far- off purring, her warm belly and comforting smell. He knew he was with her once, and then he woke up to the cold world of Tom and Mary and the door flap. Perhaps it was this hunger that led him to the yards of families. He tended to get more attention in the yards than on the sidewalks. The ladies, Janet and Beth, put out bowls of milk for him, which gave him diarrhea, but he loved to drink anyway, kind of like the chili Tom was always making and getting sick from. “It’s so good it’s worth it,” Tom often said when he left the bathroom. Gus got that. Janet and Beth talked to Gus like he was a baby, “Ohhh we wish we could keep you.” When they were inside, their seven-year-old son, Max, chased Gus with a baseball bat. This is why Gus generally did not like children. The little ones were sometimes scared of him and ran away. Two brothers named J.J. and A.J. ran screaming from Gus every single time they saw him. Gus often rolled onto his back and stretched out on the grass to show he meant no harm, but those two always went running and screaming no matter what. That’s why Gus started hissing at them. He reasoned, well if this is what they think I am then this is what I’ll be. The horrified look on the parents’ faces made Gus feel a little nervous; what if they told Mary and Tom? But some things were worth it.

Only the strange, lonely children or the confined old people were gentle with Gus. Maddy, a teenager in a wheelchair, Alex a girl who kept bats in cages behind her house , and Mr. Giardano who walked in his driveway in circles with his walker, they always received Gus with warm hands, soft strokes, kind words. Mr. Giardano even brought canned cat food and soft treats just for Gus. But Gus knew he could not count on them consistently.

Gus was not so sure about humans. He wanted one to love him, but he knew there were so many kinds of humans and so many ways they could act. Mr. Holstein slapped his wife across the face in front of their kitchen window and the wife cried. Mrs. Williams shook her tiny baby and then she cried too. She looked so scared and lonely. As he prowled from backyard to backyard, he heard many people fighting and yelling.

Gus decided to stop taking their treats of milk and soft food, returning to his empty house to eat his kibble and drink the water, sleeping in his basket by the door. He began to think he was lucky to be on his own, with a roof over his head, food in his bowl, and no one bothering him. He stopped going into the backyards, learning to steer clear of outstretched hands, not looking up at the windows. He didn’t want to see inside the other houses anymore.

Proxy

Re:Fiction, September 2019 Writing Contest, Honorable Mention

Proxy

She’s probably about twenty. Stein scratched his chin, relieved to see the woman outside his window pull out a book and not a phone from her backpack as she settled on a bench in the park across the street. His head ached from holding things in. Distracted by the jangle of keys, he heard one of his tenants entering the decrepit building, trudging up the dark stairwell.

The Stein’s shop window remained empty; he hadn’t sold jewelry in years. His mother’s ghost appeared before him, standing as she used to before his father, in this very office. Then, the business thrived; the building, their home, glistened, smelled of cooking onions.

Harry, that can wait. Come to the table. His father emerged and faded as Stein’s

mind wandered back to his last conversation with Sylvie, just on Wednesday.

Busy? He jibed at her, purposely sarcastic, pretending to fix a pipe and passively criticize Sylvie for her horrific apartment packed with stacks of newspapers, books, piles of clothes. Checking on her.

What do you care? She sniffed, shoving twisted fingers deep inside pockets in her stained pink robe.

Stein remembered a different Sylvie, young, and, at least to him, pretty. Back then, her apartment shone, neat as a pin. Her hair fell in brown curls to her shoulders. Stein sometimes asked her out for a drink, a show, a cup of coffee.

Gerry, you will not believe this.

Her South Philly accent. Touching his arm and laughing. She could do impressions of anyone she met, twisting her face into an old man’s grimace or sour Mrs. Sherwin who owned the dry cleaner around the corner.

There were other tenants, of course. People on the fringe. His rent was cheap. It had to be. The place deteriorated to dump status. He barely knew who lived there. They were all just monthly checks, hunched shoulders carrying paper bags scurrying in and out. But he put Sylvie in a different category. For one, she was his longest tenant; for another, she hadn’t paid rent in years; for another, he loved her.

He’s after me. He’s been chasing me for blocks, Gerry. We need to call the cops.

But Stein also hated the newer Sylvie. His face reddened thinking of how she often answered the door naked. She wasn’t funny anymore, no more stories.

Sylvie! Back! He screamed at her when she wandered out in the hall, half dressed, screaming herself.

You get back! She shouted at him like a stranger.

Sometimes her door wouldn’t open because of all the newspapers. He’d have to push with all his might to move it. The couch and bed and table were all hidden under piles of junk. The refrigerator door opened to a persistent science experiment, full of moldy blobs. And that smell that permeated the place. He knew Sylvie couldn’t clean herself anymore.

Oh Gerry, I’ll miss you when I am gone. That last time. He didn’t know if she was being mean or not.

Where are you going? That’ll be something. How’d we get you out of here?

Heavy with Sylvie’s absence, he observed the woman in the park. She bit her fingernails as she read.

Doctors. You’re prolonging the inevitable. She’s not even breathing well on the ventilator.

Stein stood stiffly and reached for his wrinkly trench coat on the hook behind his office door. He crossed the street and approached the young woman, wondering what he would say. She looked up with a start; annoyance darkened her face. Stein felt worse for a second, desperate, fearful she would run away.

“Can you help me?” he said. The woman moved one hand on her backpack. “My Sylvie. She’s in the hospital on life support,” embarrassed, relieved, he began to speak, at last, “I don’t want to kill her.”

The woman swallowed. “Oh. I’m…”

At the sound of her voice, Stein broke down, hacking and slobbering. The woman put an arm around the old man, stiffly at first, then more softly. Minutes later, she pulled away, and stood. Stein walked slowly beside her in silence, relieved.

Puppets

On the Edge of Tomorrow, BHC Press December 2017

I can’t focus. I lay on my bed, literally fuming. I am listening to old Pearl Jam. My feet are sticking out, Converse sneakers still on. My hands, with bitten nails, are clenching and unclenching. I just want to be left alone. That's what my life is- being alone. It works for me. Our cat, Oreo, struggles onto my bed and nuzzles my face. My mood is even too dark for Oreo. I pull away, and with that physical gesture, drag myself up and off the bed. I walk straight out the door to the long corridor, down the white carpeted staircase, through the sterile kitchen and out the front door. I know where I am going.

(Excerpted from “Puppets”)

How a Stuffed Animal Helped Us to See Our Child as More Than a Diagnosis

It’s a special kind of hell to know, or to think you know, there is something wrong with your child even before they are born…

A Sister Whose Suffering Takes Her Deeper Into Life

The Philadelphia Inquirer, May 22, 2005

Maryellen Nerz-Stormes of Strafford was selected as the archdiocese's May Queen earlier this month based on an essay about her that was written by her sister, Maggie Nerz of Fairmount. As queen, she had the honor of crowning the statue of Mary as part of the Archdiocesan May Procession in Center City. Nerz-Stormes, 46, is a senior lecturer in chemistry at Bryn Mawr College. A condensed version of the contest-winning essay, "Why My Sister Should be May Queen/' follows.

My sister Mary and I are two of seven children, she being the oldest girl and me being the youngest, with 11 years in between us. Because of her position as oldest girl, Mary was often called upon by our mother to help mother the younger children

Besides baby-sitting us and changing our diapers, she taught us to pray, disco dance, told us about high school and college, took us to movies and out to eat, and gave us advice about our own lives. Since Mary was a straight-A student who went on to get her Ph.D. in organic chemistry and a natural athlete who played golf, field hockey, and basketball, she was someone we as little girls really wanted to be.

Throughout every phase of my life, through high school, through college, through graduate school, she has guided me and given of herself for me. In college, she helped me decide about where to go to graduate school. In graduate school, she let me live with her family and gave me a car to drive. In my working life, she has given advice and support.

Like the Blessed Mother, whose love is often an invisible force of support, my sister's care is like the air I breathe, always there in abundance, whether I know and appreciate it or not.

The most current chapter in my sister's life and the life of our relationship is perhaps the most poignant reason why she should be May Queen. My sister was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer four years ago. When it was discovered, the cancer had already spread from her breast to her lymph nodes, bones, and now brain. She has · undergone aggressive chemotherapy, receiving two drugs a week, every week, since her diagnosis. She has had the two tumors in her brain treated with radiation twice.

Throughout her illness, she has kept her job as a teacher at Bryn Mawr College, teaching hundreds of students organic chemistry while , suffering with the many side effects the different drugs have caused. She has taught with constant stomach problems, with her fingernails falling off, with her bones aching, with ~he permanent loss of her hair, and with the constant anxiety, and days of hopelessness brought on by fighting an incurable disease.

My sister has been a fearless and active participant in her treatment, realistically facing the implications of her prognosis and working with her doctor to make the· choices that will extend her life the longest. She has taught herself oncology and how to read her own scans, reads medical journals voraciously, and researches the different treatments out there to the best of her ability. Her sole purpose is to extend her life for her two sons, a blessed mother in her own right, indeed. On top of all this, she has taken what she has learned to advocate for others, and seriously sees this as part of her mission.

Like the Blessed Mother's famous "Yes!" to the request made by the Father to bring Jesus into the world, my sister has also said "Yes" to the call of God by letting her suffering take her to a deeper experience of life. She has spent more time with her sons, reading with them, advocating for them, mentoring them, loving them. She has joined her church choir, volunteered at a free clinic, taught her students how to knit, become an extraordinary and prolific painter, and is working on a book about her experiences. She has translated her more palpable sense of lack of certainty about the future into what she calls "cancer time," an excuse to give more abundantly and generously; more impulsively and fearlessly. If you know my sister, you know that a gift of flowers, a hand-knit scarf, a b1·ownie, a donation of time or money, a hug, a kind word, a direct and caring look in the eye, a loving note, is probably in your future.

In my own relationship with the Blessed Mother, I often meditate on the mere fact that Mary was asked to bring a child into the world and then asked to share him with all of humanity, and then asked to watch him not only die, but be killed. I often focus on the level of giving up the Blessed Mother was called to live out, and I try to comfort myself by thinking of Mary's sacrifice, when I struggle, as my sister does, with not wanting to give up the smaller things I am asked to give up.

I think I was most drawn to writing this essay because of a conversation my sister and I had just two nights ago. We were talking about the month of May and the Race for the Cure and the breast-cancer awareness so much of us hear about through the media. We were talking about what it means to be a survivor. According to the · media-driven world, a survivor is someone who has defeated cancer, a blond woman with a tan who is bounding off the tennis courts, triumphant over death. My bald sister is not the picture of a survivor the media want to advertise, yet she is the ultimate survivor to me. · So much of what we are called as Christians, particularly as Catholics, is countercultural, and I think my sister's form of being a survivor is countercultural, even and especially within the world of cancer, where it should be most valued.

So much like the Blessed Mother, whose unhesitant "Yes!" changed the history of the world without anything in it for herself, my sister has said the same kind of "Yes!" again and again and has redefined surviving for me, and hopefully the other people who have had the luck to experience her bright-shining, never-dimming light of a life.

Maryellen Nerz-Stormes (right) of Strafford was named the archdiocese's May Queen on the recommendation of her sister, Maggie Nerz (left) , who wrote of her older sibling’s early guidance and recent struggles with breast cancer.

Small Craft Warnings Collection

Published in Small Craft Warnings (Swarthmore College), 1999, 2000

Season (1999)

It gets dark fast this time of year

the old man behind me said as

we moved together backwards

approaching the city center

We hate darkness, I thought

especially that which comes early

We hate rising in it and retiring in it

seeing light only through panes

begrudgingly

We hate summer too, we say,

the heat that leaves us sweating

slouched on platforms

fanning ourselves slowly

In winter we are only death at our desks

Pushing white paper around

The trees have been brown too long we yawn

Spring spring we chant, looking forward

to that which is warm, colorful

Searching for tiny purple buds edging the path

from the station we point and

say there’s one excited energized

by daylight we earned

we saved for so carefully

Close (1999)

In the heavy heat of almost summer we walked without destination,

city block by city block, roaming the interior of our neighborhood.

North south east west we walked pavement lying flat or cracked

in need of replacement in places or shifted like mismatched lips.

Looking up through sodden air I noticed the sky still blue,

daytime with the lights turned out,

saw the clouds move in bunches surrounded by this strange night blue,

The starless sky has clarity without light, I thought.

Processing in this lightless light we entered alleys,

saw white roses spilling out over the tops of fences,

looked up at your old window, watched the hyacinths growing

From a flower box outside a rowhouse door.

Entering and exiting smells, the flowers, exhaust, the bodies passing,

restaurant food cooking, the garbage in dumpsters rotting,

snug in the humid air, the airless air,

passing through it slowly, as it required,

we walked the middle of streets,

looping around behind buildings standing straight

or crouching beside lampposts above blacktop,

returning to the same conclusions again and again.

We crossed at lights, stop signs, when we wanted to in between.

We talked, pointed at places we knew.

We walked in silence

moved further into our neighborhood,

inside the heat, circling the center,

peering in to what is hot about heat.

Lights, garish convenient store lights,

Sirens, car alarms, voices from tables

defined our small exchange,

our purposeless journey.

Christmas Poem

For Mom and Dad

You do not know about

the lights on Rittenhouse Square

the way none of us saw them coming

and a few of us suggested they were a miracle

They hover in the trees-multi-colored spheres

I search to see if they line the entire park

My heart feels all there is to feel

when one is overwhelmed

by excess, but still wants more

No, you do not know about

the lights on Rittenhouse square

or my throat gone tight as it does

by the silliest things

the moon in a sliver or

perfectly round and orange

the bus coming when I want it to

an arm's smooth stroke through water

when, in that first feeling moment

I think of telling it

of how to tell someone about it

I think of telling you about it

Maybe I will forget to tell you

about the lights on Rittenhouse Square

How they remind me of everything

and nothing at once

how they seem to be like small planets

I can imagine reaching for

to cup in pale hands

How they take my eyes in their possession

pulling them upward

pushing heat through my chest

like hot water through pipes

revealing for a second

life turning slowly

dangling from something a

as fragile as a branch

Ferris Wheel (2000)

The ferris wheel across the bay

was spectacular at night.

I could not detect its movement

from the dock where we swayed

in the tumultuous wind we marveled at,

were slightly afraid of.

I held hope that it was something great

to see moving slowly, consistently,

something so perfectly round and

brilliantly lit.

The man who was here

a few days ago

was the first I heard mention it.

Pointing a broken telescope its way, he said

Let’s see if we can catch that ferris wheel.

My ears perked up instantly,

not caring at all for broken telescopes

you said were broken your entire life.

It was the words ferris wheel that caught my ear.

I did not see it until three days later,

at night,

with raw eyes, without magnification.

Surprising myself at feeling sad

and alone seeing the lights so far away,

feeling the wind again blowing hard,

knowing all the miles of ocean and beach

darkened and deserted were close,

the families I do not know by the dozens

coming and going.

The waves have always brought forth in me this

precious sadness

Longing thoughts of a perfect like, b

ig things with smallness beside them.

A house by the sea.

I have had to take deep breaths, hold my throat tight,

Emotion matching the tireless

disappearance and return of the bay.

The ocean is a thing that doesn’t change,

yet is always changing

nags, whispers in ears again and again

There is something else here, something else,

Either surrounding, holding us up to float, or

hitting hard, salt water waves breaking, or receding

skulking out to sea,

draining the bay into thick mud,

Small puddles, leaving

tiny flies that sting or the

worms that you pointed out,

poking their heads up,

first one then hundreds,

visible from the light

of the house behind us. PASTE POEM HERE

Commonspeaking Collection

Published in Commonspeaking (Swarthmore College), 1999

A Sleeper Car (1999)

You are asleep with your small glasses folded up, grasshopper legs.

I squint out the window to see flat land, shadows of darkness,

am convinced that I have never known anything about this country.

There is the steady chug of the train moving forward in the night,

your steady breathing filling the car, your relaxed knee, bare foot,

moonlight reflected from the ring you never remove.

Another train passes so I could reach out and touch it,

headed someplace faster it seems. Somewhere where

they are not I suppose sleeping time away, meandering down

narrow corridors unsteadily, chewing slowly, digesting well.

I see your shirt hanging on the door

swaying slightly as the car rumbles onward

convincing me that I never knew anyone before you.

I let the curtain fall, smothering the moon,

the wide light that pulled me

from sleeping beside you

Salad Days (1999)

For my parents

We had a strawberry patch in our big

green, brown, and forsythia yard

beneath the pealing blue moon with

white trim and dark eyes

We lived above a tennis court never built,

left an ambiguous pit overtaken by daisies

The pines bowed courteously

beneath their skirts we dined,

silverware, bright pink and green

plastic baskets left over from Easter,

baby dolls with heavy eyes

We had a banging back door,

cracked wooden steps

The ground felt uneven beneath our feet

The grass held hidden treasure

The weather, sometimes grey and sometimes blue

sometimes warm and sometimes cold

We knew no schedule

The woods, soldier friends lined up

A tree house held low in a crook

an arm snapped

Injury never healed

A path meandered downward

dotted by protruding tops,

buried bottles

Memory reflects the shimmer of metal

A colander in the late spring, early morning sun

We picked our berries knowing

the devouring would wait

past pump, past blackeyed susans, a pear tree

a hose wrapped up like a snail

We returned to the moon which awaited us,

disappearing, fading into its cool shadows

Redtree Collection

Published in Redtree (Bryn Mawr College), 1994, 1995

Tomatoes, Elvis, and the Beatles (1994)

Tell me you were

not always dead.

Tell me I was careful-

I picked your face

ripe and fat,

a tomato from

a drooping caged vine.

Insist I pulled it

plump, that I spoke

so softly, that I refused

to risk the slightest

impression.

Tell me your

red skin was once

that supple, that

sensitive.

Did I,

in some

spoiled fit

kill you?

With a twist so

sharp, with a hand

so huge, I crushed you

and squeezed

you shapeless.

Could it have been me?

Was I the culprit

who poked and

peeled you

to a splotch,

a puddle of

seeds and pulp?

Perhaps you were

neither alive

nor dead, you

were a seed

I forgot to plant, you

were the flash-fear

of a potential

stain, you were

green and window

sill bound.

Yes, you were

neutral and I

was indifferent.

I imagine having

not picked

killed, or ignored you.

I fantasize you

fallen, wasted

overripe, a taste

bitter and

dark, gravity your

only murderer,

a merciful undoing.

Tell me it is

good that you

seemed always dead

(like Elvis) or

always broken

(like the Beatles)

that I found you this way.

Our relations could be

a sighting,

a flash of sequins,

a cape, an impromptu

reunion,

so singular, fantastic,

and unreal

that they exist

forever in

dispute.

Linzer Hearts

puff up so big and white in this heat,

voluptuous, untouchable.

Back on countertop they withdraw

to factual selves just a

little better than disfigured.

Reality has set in and has

relaxed them to disappointment,

rationalized them to rightness.

They lie on wire racks,

cooling in cooperation, never

resisting jam spread between

their doubled selves, sides

which have somehow failed.

And as brown edges deflate,

awaiting a shower of white

felt like rain on a roof two

stories above, a subtle

shock on top, memory slides and

perfection reaches a pleasing distance.

The jam, a sweetness without teeth,

the remnants of the young woman stuck

inside who knows her body has not lasted

who knows all were is really is

the warmth of sun across

one’s face when clouds

come apart.

Miss Rumphius

Living to be old enough to have

little children circled around your feet,

crumbs dangling from their lips,

eyes wide and fearful and reverent,

you sleep alone and easy at night,

knowing you always kept your options open.

Looking down at a body laid out wake-

straight, covered like a good story-book

lady in patchwork, topped off with a head

of skunk-striped hair, you are blue

from the day in day out of watching

the sun and moon switch places.

Their consistency mocks your options,

their push and pull of the seasons,

the waves, puts the freedom

felt from globe-trotting

to shame.

No island king or fresh fruit could

keep you, your body nagged and you came

back, the sea which spat you out

swallowed you whole, the roses and

purples and violets invited you,

intoxicated, and put you to bed.

The third thing, which you

placed hesitantly on

a back burner, did not need

you, came to life on its

own, blended in to

the clock-work of stars and water

right under your window

sill, beneath your nose,

seeds blown by a wind stronger

than any body, any suitcase full

of souvenirs.

Large and legendary,

it is your name which

precedes you, outrageous

amongst the sparseness of a

small house by the sea.

Having accomplished your tasks,

having lingered above the dusty skies,

the backgrounds you filled in long ago,

sitting solid amongst these colors so

real you could eat and drink them,

you look as though this was not a

matter of choice, that there

were no real options.

You remain here as if only to

prove that a whole summer spent

throwing seeds to the wind is

not a whole summer

wasted.

Scraping Plates

Published in Musomania (Bryn Mawr & Haverford Colleges), 1994

Scraping Plates (1994)

This is love -

common as a sink

full of soap and water,

warm and rubbery,

soiled and lovely,

awful and diminishing.

This is all that has

happened between us-

trapped in the forever

shallow end,

continuously waiting for

the plug to be pulled,

innocently admitting a

tendency to run

away as quickly as

It came.

Come in come in

it calls to

weak hands which

obey each time.

Opposed twins,

reaching for the

same things,

simultaneously they

recall the truths:

the blue of two fixed eyes

the sorrow of second best,

the sincerity of sadness

all over again.

If words do not work,

sensations will.

A squeeze of a sponge

soaked with these waters,

a trickle of pitiful heat

across a stiff back,

all that is needed to

swallow the shiver which

startles straight through

This water is mine, I swear,

contained in square, submerged

in countertop.

I appear in the clear left over

when suds separate.

I indulge in the elusive

putrid and vibrant of bubbles,

colors which stain memory.

With my hands in the thick

of such love I could forget

the huge of the house around

me, the fact that water always

washes somewhere, and warmth

inevitably fades to cool.

I am fixed to this spot.

I am a creature with two

good legs and garden hoses of

veins and intestines all my own.

I am fixed.

This is

love

this flood,

winding its way

around fingers,

threatening circulation.

This is all that has

happened between us,

this steam rising to face like

fever, addictive

and agonizing,

consistent in its

promise to

break.

Dye Job

Published in Uses (Villanova University), 1992

Dye Job (1992)

Get a dye job-

a polident, liposuction

dye job.

Take those strings woven

into your ritzy wig and

get a dye job.

Dye red-a deep, fire

Lucille Ball-technicolor

red.

I’ll do it for you.

I’ll rub that bloody goo

into your scalp and we’ll

watch it swirl down

the drain.

The dye job should

go without a hitch.

So get a plastic pump

transplant-get your veins done.

Scream over the

vibrating boob tube

from the kraftmatic adjustable.

Curl up in a tanning bed

-bake at 375-

you’ll come out lovely,

lovely and brown,

as brown as your

dye job is red. PASTE POEM HERE